College athletics at a crossroads over compensation

August 24, 2022

August 24, 2022

Are Division I student-athletes employees of their respective institutions? And should they be paid beyond full athletic scholarships?

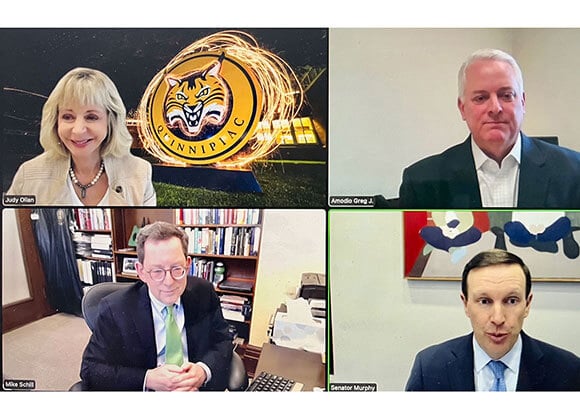

These were some of the questions posed recently by President Judy Olian, University of Oregon President Michael Schill, U.S. Sen. Chris Murphy of Connecticut and Director of Athletics Greg Amodio during an hour-long discussion titled, "The NCAA and the Supreme Court." The conversation was part of the president’s virtual speaker series, “The Way Forward.”

Schill, who also serves as chair of the Pac-12 CEO Group, insisted that student-athletes are not university employees. He asserted that student-athletes are fairly compensated with full athletic scholarships, including tuition, fees, books, room and board, comprehensive healthcare and other benefits — an annual package worth about $150,000 per student-athlete at Oregon.

Murphy, however, disagreed with Schill’s interpretation. He argued that student-athletes should be allowed to unionize and earn more than a full scholarship. This view became the cornerstone of his June 2021 legislation, the College Athletes Right to Organize Act, which was introduced in the Senate with U.S. Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont.

“The Way Forward” panel discussion was based on last summer’s unanimous U.S. Supreme Court decision in the NCAA v. Alston case. The nation’s top court upheld lower court rulings declaring the NCAA violated antitrust law by prohibiting student-athletes from earning income from their name, image and likeness (NIL) and other economic opportunities.

The Court’s decision gave student-athletes exclusive access to a brand-new revenue stream. On July 1, 2021, the NCAA issued an interim policy that paved the way for student-athletes to profit from their brands.

For example, student-athletes could suddenly sell gear with their own logo and the university’s trademark. On July 2, 2021, former Syracuse basketball player Buddy Boeheim became the first student-athlete in the NIL era to achieve that feat, according to Forbes and Sports Illustrated. Boeheim also cashed in on some commercials for a local apple orchard and a cereal company.

Murphy believes student-athletes deserve a share of the multi-billion dollar pie that generates millions of dollars each year for schools competing in “big-time college athletics” such as the member institutions of the Power Five conferences — the Pac-12, the Big 12, the Big Ten, the Atlantic Coast Conference (ACC) and the Southeastern Conference (SEC).

This summer, the stakes soared even higher with news that Los Angeles-based UCLA and USC will join the Big Ten in 2024. Couple that with Notre Dame’s independent football status up for grabs — or, at least, up to the highest bidder — and college athletics is racing toward dizzying revenue. CBS Sports recently reported that Notre Dame is seeking a TV deal worth at least $75 million per year from NBC, which owns the Fighting Irish’s broadcast rights through 2025.

But sometimes, the winners aren’t the biggest schools with the biggest budgets, Olian suggested. Sometimes, the winners are the unexpected heroes from Jersey City, New Jersey.

Last March, Saint Peter’s University — a member of the Metro Atlantic Athletic Conference like Quinnipiac — stunned eight-time national champion Kentucky in the first round of the NCAA men’s basketball championship. The Peacocks ultimately became the first No. 15 seed to reach the Elite Eight of March Madness.

It was a memorable run for the latest Cinderella story in the NCAA tournament. But for every Saint Peter’s, there are Final Fours loaded with college basketball’s blue bloods. Last season, it was Kansas emerging as the national champion from a Final Four that included Villanova, Duke and North Carolina.

There is a significant difference between the Power Five programs that play college basketball and football at the highest level with professional-caliber facilities and the mid-major Division I institutions such as Quinnipiac that do not sponsor football programs.

How significant?

Consider: For the 2020 fiscal year, the Big Ten paid Ohio State, Michigan and its other senior members $54.3 million as part of its revenue sharing deal, according to USA Today. Big Ten newcomers Maryland and Rutgers received reduced shares of $27.6 million and $11.4 million, respectively.

Likewise, the newspaper reported, the SEC paid Alabama, LSU and its members $45.5 million each, followed by the Big 12 with checks ranging from $37 million to $40.5 million, the ACC with checks ranging from $30.9 million to $37 million, and the Pac-12 with average payouts of $33.6 million.

For Quinnipiac, competing in the MAAC with other mid-major Division I institutions that don’t play football, the revenue transactions are far less lucrative. There is some minimal distribution from the NCAA. In fact, it costs Quinnipiac money to compete in the MAAC with annual membership dues and other expenses.

Although QU has built some of the top facilities in New England over the last 15 years with the People’s United Center, the Quinnipiac Soccer & Lacrosse Stadium and the Quinnipiac Field Hockey Stadium, balancing the athletic department budget with superior academics, while maintaining a top-tier presence among MAAC schools and other mid-major competitors is a challenge.

As Quinnipiac’s director of athletics, Amodio crunches that corollary every day. But when the stakes are so high in “big-time college athletics” with issues of equity, access and opportunity, Murphy doubles down on his antitrust position. Full scholarships aren’t enough.

Murphy called the NCAA’s current revenue distribution model a “fundamental economic injustice” during the panel discussion.

“There's no industry out there like this one where there's this much money in the industry, and there’s a pretty hard cap on the amount of money that the most important laborers are reaping from that,” Murphy said, referring to the student-athletes.

“I do categorize it as a civil rights issue,” he added. “You can’t ignore the fact that especially when it comes to big-time football and basketball, these are largely African American players, and these are almost exclusively non-African American coaches.”

Olian recently addressed the disparity between the Power Five schools and their mid-major counterparts in an opinion piece written to other university presidents.

“The dust has not yet settled on these issues. Yet, we can already see that an inevitable divide is emerging between the handful of big-time, revenue-generating programs participating at the top of Division I, and the vast majority of schools who self-fund their athletic programs,” Olian wrote.

“The reality is that some student-athletes among the high-profile sports in the Power Five programs have become quasi-professional athletes, competing with — and against — the majority who are true amateurs.”

While Schill acknowledged that there’s work to do and a successful outcome will require a committed, collaborative approach in college athletics, he denied that Oregon is a proving ground for aspiring professional athletes.

Rather, he said, it’s an institution of higher learning with a higher purpose, much like QU.

“I don't think Oregon is a feeder school to the professional leagues,” Schill said. “I think our students would like it to be. You have 100 or maybe 120 people on our football team. They all think that they're going to end up in the pros.

“But they’re not, right? Maybe a handful will end up in the pros ... and the rest are going to be able to go out and get a job — and that is where I want to focus on,” Schill said. “I want to focus on the educational process. Professionalizing or calling us professional is just diminishing that connection.”

Quinnipiac Today is your source for what's happening throughout #BobcatNation. Sign up for our weekly email newsletter to be among the first to know about news, events and members of our Bobcat family who are making a positive difference in our world.

Sign Up Now